The Local Sustainability Plan: in action

The Local Sustainability Action Plan has arrived.

It crept in quietly. It arrived with a deadline, aims, a set of pillars. It arrived with expectation.

And almost immediately, the conversation shifted to compliance.

Not because anyone lacks care. But because schools are used to documents that land heavily. We have learned to hold new initiatives at arm’s length until we know whether they will float or fall like a lead balloon.

And although I sympathise with leaders over this demand, especially for leaders in small schools, what if we view this as an opportunity to bring our curriculum closer to the door?

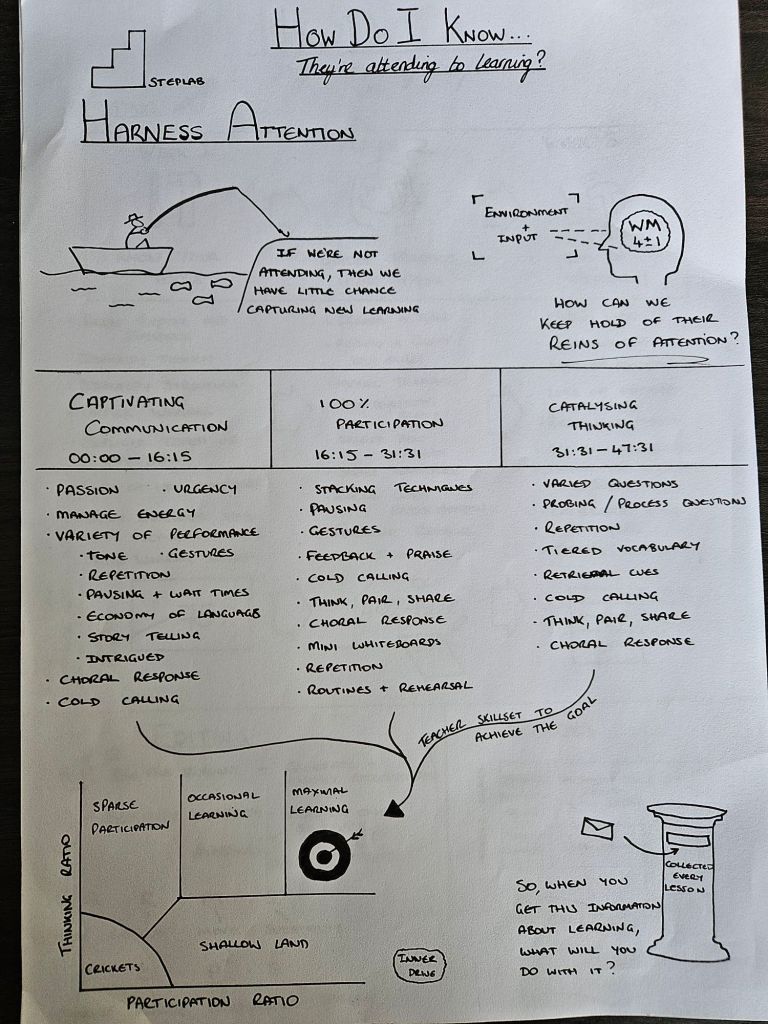

The DfE sets out in “Sustainability leadership and climate action plans in education” the follwing 4 key pillars:

- adaptation and resilience: how the setting is preparing for and responding to the impacts of climate change

- biodiversity and nature: efforts to protect and enhance nature and wildlife within the setting and its surroundings

- climate education and green skills: how learners are supported to understand climate change, sustainability, and develop relevant skills

- decarbonisation and net zero: actions to measure and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, working towards net zero

You’ll notice these pillars, the first 3 at least, are mentioned in the Geography and Science National Curriculum, so why another action plan looking to promote the knowledge and skills around this? Well, it’s more about an organisational action plan (scroll to the bottom for a simple compliance checklist to get you started) placing greater accountability on schools. However, is this a key moment not to look at these through separate lens?

I have been thinking about that weight.

Recently, after a conversation with our Sustainability and Geography lead, I found myself feeling more interested in what we might miss if as leadership, we treat it as simply another requirement, especially as we have a number of school priorities to be working on.

So why does this feel different?

Perhaps because this is not really about curriculum coverage. It is about accountability. It is about visible action. It is about whether what we teach ever quite touches the ground.

Here is the uncomfortable truth:

If our pupils can explain melting glaciers in confident detail but cannot improve the street outside their own school, then something has not quite connected.

They have knowledge.

But not agency.

And agency is the point.

Glaciers matter. Of course they do. They hold the climate story in frozen form. But glaciers are distant. For a ten-year-old, they might as well exist on another planet. The pavement outside the school gate does not. The drain that floods every time it rains does not. The strip of neglected soil by the fence does not.

When sustainability lives only in distant case studies, children inherit anxiety, fearing doom for their planet, their future.

When it lives in reachable places, they inherit responsibility.

I wonder sometimes whether we mistake scale for significance. We design assemblies about the Amazon rainforest and carbon neutrality by 2050. Meanwhile, the playground bakes in June and puddles in November. There is learning there, immediate, measurable, unavoidable learning, but it requires us to look down before we look out.

A whole-school action plan could be another laminated document. Or it could be a compass.

Not something additional.

Something orienting.

What if Maths lessons counted the school’s own energy use before calculating global averages? What if Science measured the heat difference between grass and tarmac in the playground before modelling climate graphs?

What if Geography mapped the flood risk of the streets pupils actually walk each morning?

An AI chatbot can explain the water cycle. It cannot explain why the drain outside Year 4 overflows every time it rains.

Local knowledge resists automation.

Purpose resists apathy.

If this plan is to work, it cannot survive only in a Tuesday afternoon slot labelled “Sustainability.” It has to seep into the everyday. It has to become the question that lingers (scroll to the bottom for some practical ideas):

Why is that patch of ground bare?

Why are there no bees here?

Why are the lights on?

Small shifts begin to matter.

A class counting what ends up in the bin. A group measuring classroom temperatures across a week. A child noticing that concrete holds heat long after the sun has gone down. Not as an activity for display boards but as a habit of seeing.

And perhaps the shift is not only for pupils.

If we expect children to think sustainably, we must model it. Environmental sustainability and human sustainability are not separate conversations. A school that runs on exhaustion and excess paper cannot convincingly speak about net zero.

Sustainable leadership

Sustainable leadership might look quieter than we expect:

- Fewer unnecessary documents.

- Clearer “go home by” expectations.

- Meetings that protect daylight hours.

- Procurement choices made with care rather than convenience. Not dramatic gestures, steady ones.

The strongest schools will not be those with the most polished sustainability document. They will be the ones where the front of the building tells a story. Where the garden grows. Where the community notices that something is different. By connecting curriculum, estate, and community, we transform eco-anxiety into agency. Geography is no longer about distant glaciers or faraway rainforests alone; Science and Citizenship are no longer abstract concepts. Learning becomes immediate, actionable, and relevant — grounded in the places pupils know, care for, and can change. Sustainability becomes not just what we teach, but what we live.

Because that is the real question this plan places in front of us:

What is visibly better, here, because we chose to act?

If the answer is nothing, then the document has floated briefly before settling heavily. Another initiative absorbed.

But if a drain flows more freely, if a patch of earth blooms, if a street plants one more tree because a child asked why it could not, then the plan has done what policy alone never can.

It has moved from paper to place.

And that, perhaps, is where sustainability truly begins.

Practical Classroom Shifts: Making the Immediate Unavoidable

Many schools have an eco-team which is brilliant, and I know all too well how hard it is to ensure this club has momentum, quite often happening during teachers lunch time. But how else can propel these well-meaning actions across the entire school.

The Five-Minute Footprint

Trace the journey of a glue stick, a school jumper or a whiteboard pen:

• Where was it made?

• What is it made from?

• Where will it end up?

Playground Data Walls

Create a live display of:

• Weekly litter counts

• Biodiversity sightings

• Rainfall data

• Classroom temperature readings

The Alleyway Audit

• Observe – Map a square metre of neglected ground.

• Analyse – Measure heat differences between concrete and grass.

• Act – Propose a micro-fix: planting cracks, adding shade, trialling reflective paint.

• Advocate – Present findings to SLT or governors.

• Sustain – Monitor change over time.

Engage the Council

Audit the nearest park, pathway, or even brown spaces that are redundant. Identify biodiversity gaps. Invite council representatives to hear pupil proposals for suggested developments and how they might engage and support these areas, or perhaps suggest support school projects that could influence the local community directly and encourage families to engage more.

Partner with Neighbours

Survey the street:

• How many paved front gardens?

• Where could planters increase green space?

Launch a “Green Front Door” initiative encouraging one additional plant per household, or grow and donate plants for the community, or create leaflets regarding minimising waste with suggestions on how to reuse common wasted householdd items. The school becomes a catalyst, not an island.

Green the School Frontage

Audit the front of the school – what message does this give and what does it show about the school’s priorities. Replace small areas of tarmac with planting, install window boxes or signage to promote the impact of pollution and to find alternative methods of transport. Ensure the entrance tells a story of care.

Think Vertically

In inner-city settings, ask:

• Could a roof garden be safely developed?

• Could walls host vertical planting?

• Could bike sheds incorporate sedum roofing?

Small but Powerful Cultural Nudges

• Purchase one indoor plant per term to build greener shared spaces and support wellbeing.

• Incentivise biodegradable lunchbox packaging.

• Run pupil-led social media campaigns promoting sustainable swaps.

• Track and celebrate waste reduction publicly.

Change becomes visible. And visibility sustains momentum.

Real Roles for Pupils

Titles matter; but agency matters more.

• Energy Monitors recording daily meter readings.

• Temperature monitors tracking trends across school.

• Waste Auditors analysing bin samples.

• Travel Analysts surveying commuting patterns.

• Biodiversity Stewards maintaining habitats.

The “Tomorrow” Toolkit: 3 Quick Wins

- The Bin Audit: Have one class count how many pieces of plastic are in the “general waste” bin after lunch.

- The Light Switch Challenge: Assign a someone to ensure all screens and lights are off during assembly.

- The ‘Why’ Walk: Take 10 minutes to walk to the school gate and ask pupils: “What is one thing here that helps or hurts nature?

The “Action Plan” Compliance Checklist

Use these five steps to ensure your local mission meets the DfE’s national expectations as the basis for your school sustainable development plan to build upon:

- Nominate a Lead: Ensure you have a named Sustainability Lead (this can be a staff member or a Governor) to oversee the strategy.

- Establish a Baseline: Use your Energy Monitors and Waste Auditors to get a “Month 1” reading. You cannot prove a reduction in carbon or waste if you don’t know where you started.

- Update the Risk Register: Incorporate your “Alleyway Audit” and Flood Mapping into the school’s formal risk management: this satisfies the “Adaptation and Resilience” pillar.

- Evidence the Curriculum: Keep a “Curriculum Compass” log (like the one mentioned above) showing how Science, Maths, and Geography are meeting climate education goals through local action.

- Set an Annual Review: Schedule one SLT or Governor meeting per year specifically to review the progress of your Sustainability Action Plan.