We all know and understand the importance of careful, well-thought out planning and preparation that lays the stage for the magic of learning to happen.

I remember early on in my teaching career, I would spend a long time ensuring I had mitigated against the potential barriers to learning as well as the step-by-step progression of what I felt was needed (i.e. different types of questioning; appropriate tasks; effective deployment of TA etc.) in order for the intended learning outcome to be obtained. The lesson begins: I am feeling confident, prepared and determined I will shape the children’s learning one step further. However, mid-way through this particular writing lesson (generating vocabulary for a stimulus), I am struggling for contributions, needing more hands up, noticing the haze casting across the children’s vision. Fearing the lack of engagement, I provide some words in the hope this snow balls further, but no, it was like trying to get blood from a stone – engagement for learning was going down like a “lead balloon”.

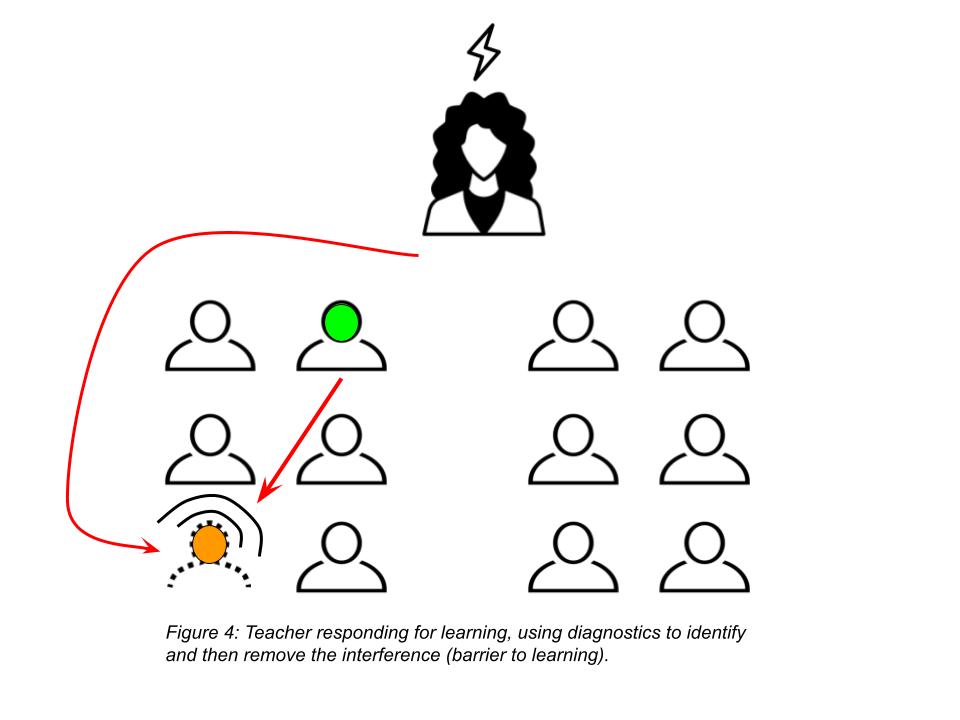

Although there are a number of things I would do differently knowing what I now know from the abundance of research that is readily available to us all, I have found across my career, in both a teaching and leadership capacity, that these mid-lesson crisis moments happen. Quite often, this comes down to focusing too much on What do I need to do? as the teacher, rather than What do they need to do? as the learner. We need to blow engagement back into that balloon.

My general recommendation for a starting point would be the following:

- Teach 3-5 minutes;

- Practice (learner to digest/ have-a go) – Individually or in partners;

- Check understanding – questioning, discussion etc. (general consensus);

- Teach 2-4 minutes OR address (if needing to address, go back to step 1);

- Practice;

- Check understanding – (general consensus);

- Independent practice;

- Check understanding (individual);

- Prepare to address (if needed) or extend.

The above would only be a starting point as these timings would change depending on the content and context; however, this process is generally a good starting point.

Indicators

First, we need to be aware of the indicators to check attention is present. This is what I like to call “Response for learning”. That moment when the deafening silence absorbs the children and dampens your spoken word. You’ll notice children begin to gaze across the room, doodle, perhaps hand-on-face, lowering themselves into the chair. Or perhaps in a group scenario, you notice passive learners, sitting back, with those more confident running the show. More often than not, the temperature in the room has increased; you’ll notice jumpers off, sips from their bottle, fanning themselves in extreme circumstances. And when you do start to choose children to contribute (how ever long this is since they have unintentionally switched off), there’s that panic from those around unsure of what was said, by whom and in reference to what. Of course, we ideally want to be proactive with our strategies that support learning, but realistically, time does get away from us so we need to be prepared to react promptly to the above.

Culture

Teacher-pupil and peer-peer relationships are key for engagement. As I heard from Doug Lemov discussing this with Craig Barton on Mr Barton Maths Podcast, “The children won’t care what we say, until they know that we care”. For me, this is the epitome of supporting children’s learning, especially those who find it difficult to engage. When we consistently model and promote positivity for collaboration, discussion, debate and explanations, children begin to realise this is truly the expectation of the room. Be mindful how you choose children because if you regularly choose children to prove whether they are listening or not i.e. John, can you tell me what we have just discussed as you appear to be taking “notes”…, your first question to those that are timid may be perceived as a reprimand rather than a genuine question of curiosity or an invite to the class discussion.

It’s evident that effective classroom strategies sit on a bed of positive culture.

- Do the children feel safe to share?

- Do the children feel valued?

- Do the children know they will receive immediate feedback because you want them to improve, not just because they are wrong?

- Is your body language and are your facial expressions welcoming and inviting?

- Are you modelling how their answers can be used and responded back into the class or into the learning process?

Using some of the strategies below will contribute to this learning culture and hopefully begin the journey of shifting motivation from extrinsic to instrinic, with the hope of shifting from performance orientation to mastery orientation (Pintrich, 2000, cited in Kirschner & Hendrick’s (2020) ‘How Learning Happens’). You can also hear my thoughts and colleagues’ views on this book here.

Pace

For me, this is really important. With careful considerations to Cognitive Load Theory being in the quest to “Eliminate Extraneous Load and optimise Intrinisic Load” (Ollie Lovell), children regularly surprise me at how well they respond to faster inputs. This is, of course, dependent on their prior learning and complexities of the new learning, but in contrary to the complexities, if we have broken the learning down enough, it should be quicker and easier to absorb. With lesson designs, particularly like vocabulary generation and Maths fluency focus, the lesson can be moved on faster than perhaps a history or R.E lesson. Although, I would argue that you could still break down key dates, prominent figures, attributes etc. that could be retrieved, discussed, written down and explored in a timely manner. With the examples below, in some cases, I would employ as short bursts aiming for 10 seconds, 20 seconds being maximum. This helps me introduce a number of strategies throughout the lesson that keeps engagement high whilst not taking any longer than it needs.

- Partner talk (see below).

- Bounce off – Child A shares their thoughts, then they choose child B and so on.

- Choose your best 3 that you like the meaning of.

- Choose your favourite word that you like the feel and sound of when you say it.

- Which date (or fact) sticks with you the most?

- Which fact is harder to remember?

- On a whiteboard, circle your favourite.

- Point to left wall if you think X, point forward if you think Y etc.

Questioning

Similar to Dylan Wiliam’s remark about how he should have used the term “responsive teaching” rather than formative assessment (Hendrick & Macpherson, 2017), I refer to questioning in this instance as “Response to learning”.

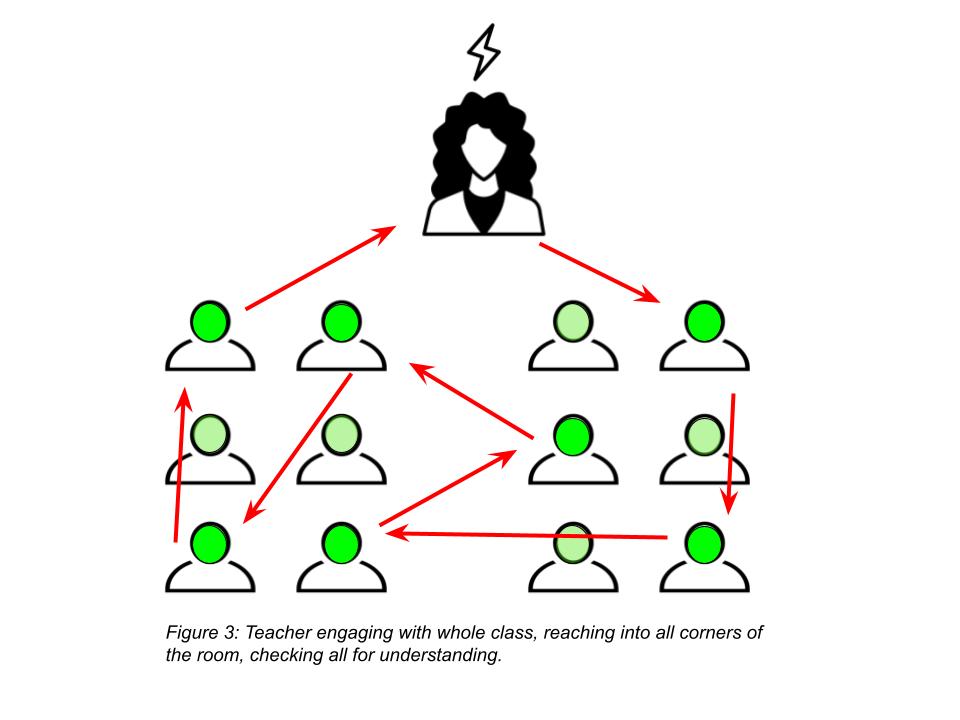

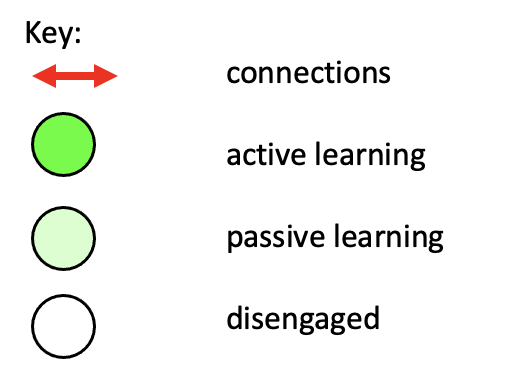

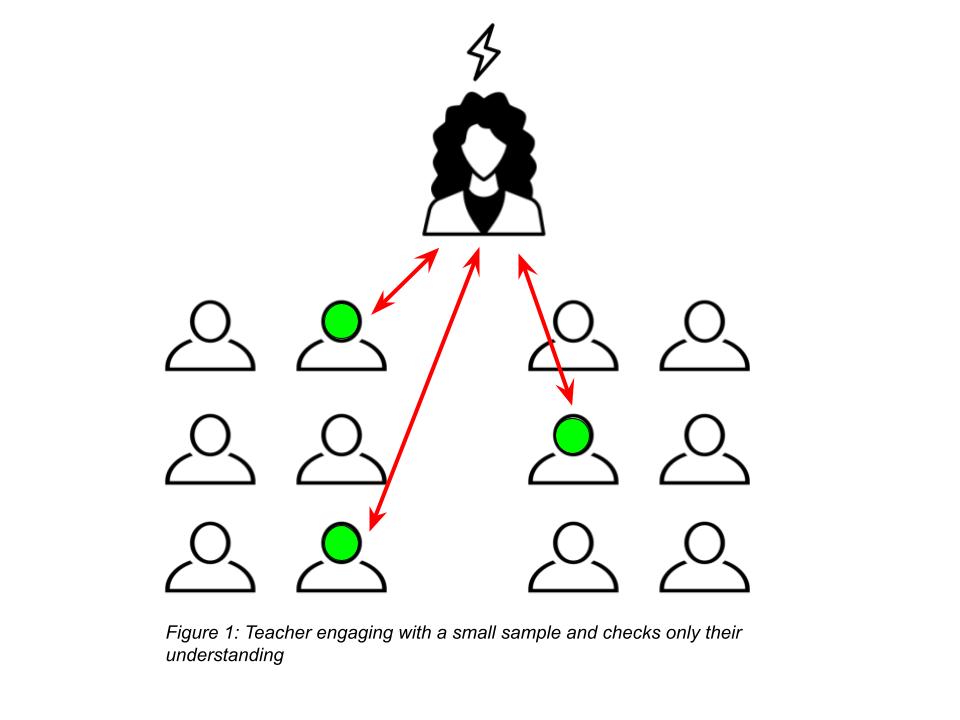

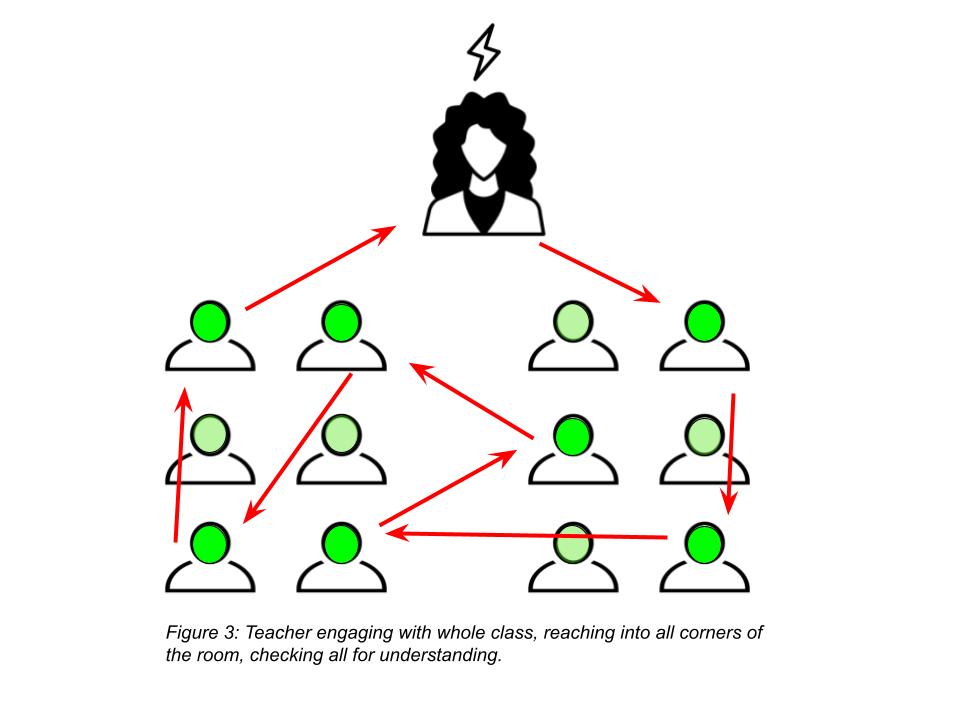

Rosenshine’s ‘Principles of Instruction’ highlights “asking questions” and “checking for understanding” as two key principles. This is crucial in determining whether the children are/were engaged in the delivery and how they have understood and interpreted (Piaget’s theory of cognitive development: ‘assimilation’ and ‘accommodation’) that information. There are a number of ways to capture this information whilst maintaining engagement. Here are just some of many:

- What is the 1 key thing you’ve remembered on your whiteboard?

- What question can you think of?

- Using fingers or whiteboard to engage in multiple choice (e.g. show me 1 finger for this word vs 2 fingers for this word being more effective)

- Why do you think that?

- Why is this better than Jane’s answer?

- What have you noticed? (patterns with number, shape; root words, prefixes/suffixes; dictators across history)

The term “cold calling” is extremely prevalent at the moment (or ‘warm-calling’ when thinking about how it contributes to culture as referenced by Michael Pershan), although the practice has existed in many classrooms for years. Doug Lemov in Teach Like a Champion explains the premise behind this and what this looks like in practice. I’d highly recommend reading the TLAC blog and checking out Tom Sherrington’s blog.

Essentially, this does link to culture. Whether you choose to incorporate a “hands-down” approach or not, creating an environment where children feel confident to speak aloud, where mistakes are welcomed and risks encouraged is what will allow this questioning approach to blossom. At first, it will be daunting and you may have to invest lesson time but it will be worth it. Consider the perseverance as ‘short term gains are for the pessimist, long term gains are for the optimist’: a phrase that resonates with me, especially in leadership.

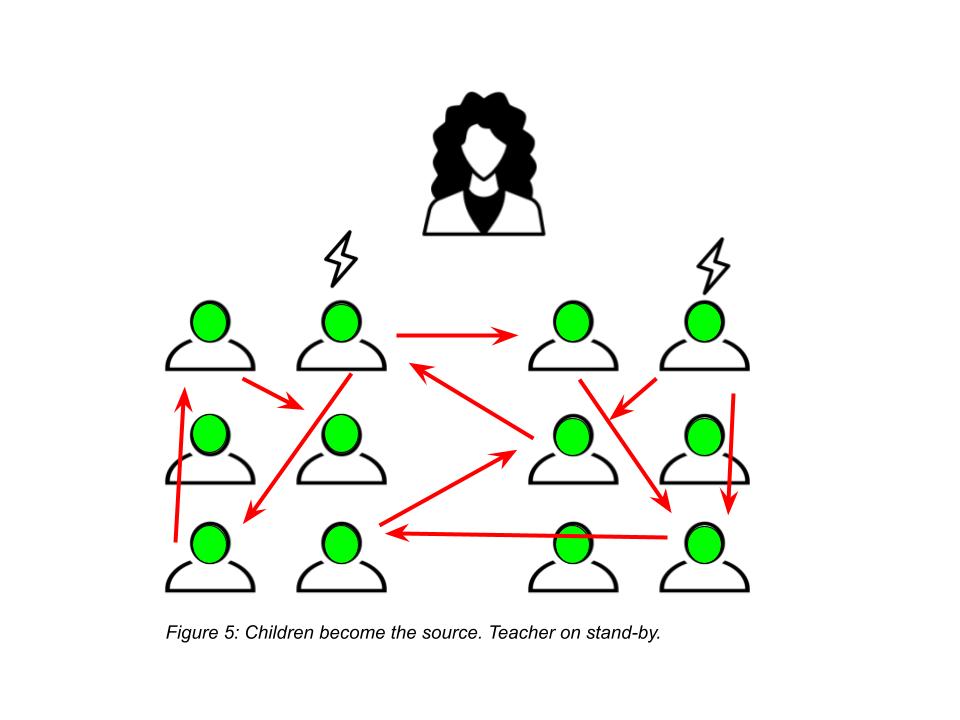

Partner talk

This is an element of cold calling but I am separating this to offer other strategies during this segment of learning. Being purposefully and already considering the seating plan, I want to encourage partner talk as another opportunity to digest. If they have understood correctly, they will regurgitate this information through their own words, providing their partner with now 2 explanations (excellent opportunities to promote oracy). This partner can then use this to support their own understanding. By sharing with the class what their partner has said will allow me to assess how well their partner has understood, how well they have understood, and taking it one step further, how well they understand by agreeing or disagreeing with their partner.

- 5 – 10 seconds, choose, discuss, agree.

- Share your favourite with your partner.

- Share your weakest or most difficult to remember with your partner.

- Give a tip to help your partner remember (it might not be the best tip, but that act of focusing on this could be enough).

- Share with the class one point your partner has raised.

- Share with the class one aspect you liked the most about what your partner has said.

- With your partner, create a sentence using the following.

- Give your partner an answer, they have to make the question.

Position

With an ongoing discussion about the effectiveness of displays in the learning environment, we are all aware that having a board cluttered with lots of examples, printed lettering and posters creates a ‘blur’ within the environment. I know if I swapped one poster or element for another on a cluttered display board, I would highly doubt anyone would notice unless using or looking at the board intensely. So by standing in the same position, I feel that sometimes we can blur into the environment too, especially when that “lead ballon” begins to lower.

Move around, get away from the “left-hand side of your board” or from behind your visualiser stand, or worse, the teacher chair, and patrol. Show the children you’re actively listening to responses, ideas and open a public forum where those less confident can ask you a quick question as you are passing by (what you do with this links back to culture).

Pause (refill the balloon)

After all of the above, you’re keeping the balloon afloat, all children are engaged but there can come a time when all that thinking and functioning of the working memory just feels too much. Pause! Give time for the children to talk with their partner to summarise, discuss and reflect: time to add air to that balloon.

I am yet to find enough evidence and research that explores what I perceive to be an example of cognitive fatigue, but what I do feel links in the concept of “Vigilance Decrement”. This is where the ability for the child to act and deal with signals (teaching input, discussions etc.) deteriorates. If children feel overloaded, learning will be hindered. So be mindful not to sacrifice learning at the expense of engagement.

Pedagogy

“We teach explicitly so I need to be telling them what they need to know.”

Whatever your views are and/or the pedagogy your school believes in, children still need to be engaged to receive the quality you are providing. Archer & Hughes (2011) in their book ‘Explicit Instruction’ highlight the fundamentals in eliciting responses: frequent responses; monitoring student performance; providing immediate feedback; and pace. Whether you prefer an inquiry approach to learning or explicit, direct instruction, you still need to employ the strategies that allow learners to learn, make sense of, deliberate, practise, question, argue and conclude.

There are a number of reasons and factors that constitute why lessons need to be teacher focused vs learner focused. Ultimately, the goal is for it to be learner focused, but I am aware of schools at different stages of their journey that need to focus on other priorities, such as behaviour, consistent teaching pedagogy etc. But, with the aim of all lessons to be effective for the learner, it is fundamental to consult your own classroom experience, experience of your colleagues in conjunction with other academics who provide a number of useful strategies. I would also recommend looking at the WalkThrus books (1 and 2) by Tom Sherrington and Oliver Caviglioli as these offer a number of useful strategies to enhance classroom practice. Use the examples above that best work for your children and ultimately, which will support the knowledge you intend the children to learn.

Have all the tools at your disposal to keep that “balloon afloat”.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly